Service Endpoints and Private Endpoints - deep dive (1/2)

In Azure, when you want to isolate a PaaS service such as Storage Account, Container Registry or Key Vault, you have a couple of options. By default, those services are accessible to anyone, who know their endpoints and obtain a key or a token authorizing a connection. Some of those require additional permissions to be able to interact with a data plane (e.g. Azure Key Vault has access policies and RBAC), but they don’t guarantee network level security. If you want to disable public connectivity, you could use either Service or Private Endpoints. As they are completely different concepts, we need to pinpoint all the differences. Let’s get started.

Playground

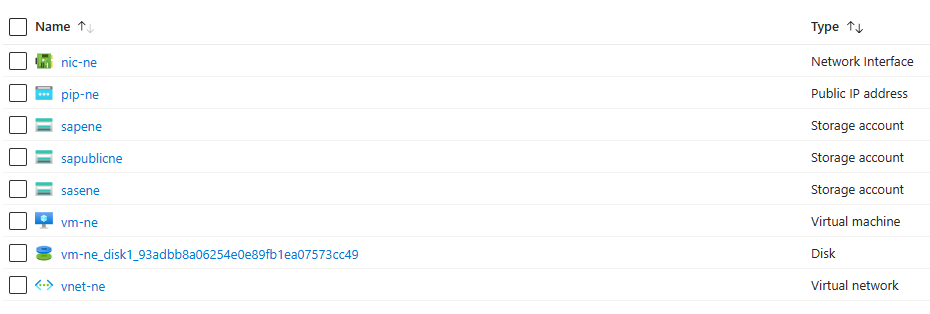

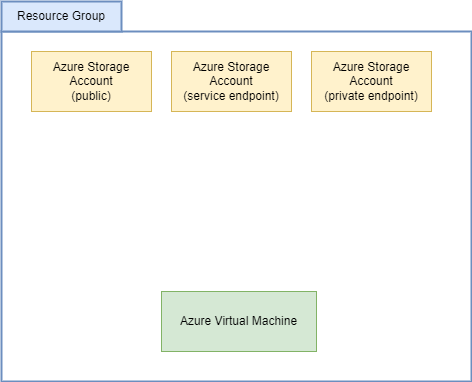

To get started, I’m going to deploy the following infrastructure:

In short - we’re going to have three separate storage accounts. We’ll try then to isolate some of them and see how they behave. I’m also going to use Bicep for deployments as we’re going to have lots of different resources to configure. The virtual machine visible on the diagram will be our jumpbox for testing accounts when they are successfully isolated on the network level. I’ll also use my own computer to test the connection whenever possible.

Initial deployment

To deploy the initial resources, let’s write some Bicep script. The whole infrastructure is going to be deployed on a subscription level, so we can create all the services at once:

targetScope = 'subscription'

param parLocation string = 'northeurope'

resource rg 'Microsoft.Resources/resourceGroups@2023-07-01' = {

name: 'rg-service-private-endpoint-ne'

location: parLocation

}

module sa1 'modules/storage-account.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'sa1'

params: {

parSuffix: 'public'

parLocation: parLocation

}

}

module sa2 'modules/storage-account.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'sa2'

params: {

parSuffix: 'se'

parLocation: parLocation

}

}

module sa3 'modules/storage-account.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'sa3'

params: {

parSuffix: 'pe'

parLocation: parLocation

}

}

module vnet 'modules/virtual-network.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'vnet'

params: {

parLocation: parLocation

}

}

module vm 'modules/virtual-machine.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'vm'

params: {

parLocation: parLocation

parSubnetId: vnet.outputs.outSubnetId

}

}

I’m going to skip the content of modules for now as they are just basic configurations with default parameters. We can summarize those though:

- as for now, each store account is available publicly

- each storage account has a single container named

test, which has public access disabled - virtual network is created with

10.0.0.0/16address space and single subnet10.0.0.0/24 - virtual machine will have a single public IP address assigned with dynamic allocation

With Bicep ready, let’s run the deployment:

az deployment sub create --location northeurope --template-file deployment.bicep

After a moment, the initial setup will look like this:

The last step to finalize it is uploading a single blob file to each storage account:

az storage blob upload -f deployment.bicep -c test --account-name sapublicne

az storage blob upload -f deployment.bicep -c test --account-name sasene

az storage blob upload -f deployment.bicep -c test --account-name sapene

Great! We’re ready to make some improvements.

Public storage accounts and private access

As mentioned before, all 3 storage accounts are currently available publicly. The blob container however, which currently stores a single file per each account, is private. We can confirm that by sending a simple HTTP request to the URL of our blob file:

curl https://sapublicne.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep

curl https://sasene.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep

curl https://sapene.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep

Each of those request should return an error:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Error>

<Code>PublicAccessNotPermitted</Code>

<Message>Public access is not permitted on this storage account. RequestId:4c28d412-101e-002a-6f97-5043b4000000 Time:2024-01-26T20:38:04.8726364Z</Message>

</Error>

Does it mean, that our storage accounts are already secure? Unfortunately not. We can easily get access to every stored file by generating a SAS token like so:

az storage blob generate-sas -c test -n deployment.bicep --permissions r --account-name sapublicne --expiry 2024-01-31T00:00:00Z

az storage blob generate-sas -c test -n deployment.bicep --permissions r --account-name sasene --expiry 2024-01-31T00:00:00Z

az storage blob generate-sas -c test -n deployment.bicep --permissions r --account-name sapene --expiry 2024-01-31T00:00:00Z

Now, when we append the generated token to the URL of each file, instead of error, we’ll get an HTTP 200 response:

curl "https://sapublicne.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep?se=2024-01-31T00%3A00%3A00Z&sp=r&sv=2022-11-02&sr=b&sig=<redacted>"

StatusCode : 200

StatusDescription : OK

Content : {116, 97, 114, 103...}

RawContent : HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-MD5: FSTNbSlPBSO94KEc+i6Hdw==

x-ms-request-id: b5fb16d7-101e-0003-7898-5035f6000000

x-ms-version: 2022-11-02

x-ms-creation-time: Fri, 26 Jan 2024 20:35:01 GMT

x-ms-lease-s...

Headers : {[Content-MD5, FSTNbSlPBSO94KEc+i6Hdw==], [x-ms-request-id, b5fb16d7-101e-0003-7898-5035f6000000], [x-ms-version,

2022-11-02], [x-ms-creation-time, Fri, 26 Jan 2024 20:35:01 GMT]...}

RawContentLength : 971

---

curl "https://sasene.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep?se=2024-01-31T00%3A00%3A00Z&sp=r&sv=2022-11-02&sr=b&sig=<redacted>"

StatusCode : 200

StatusDescription : OK

Content : {116, 97, 114, 103...}

RawContent : HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-MD5: FSTNbSlPBSO94KEc+i6Hdw==

x-ms-request-id: 5799ea52-d01e-0012-0f98-5069d2000000

x-ms-version: 2022-11-02

x-ms-creation-time: Fri, 26 Jan 2024 20:35:33 GMT

x-ms-lease-s...

Headers : {[Content-MD5, FSTNbSlPBSO94KEc+i6Hdw==], [x-ms-request-id, 5799ea52-d01e-0012-0f98-5069d2000000], [x-ms-version,

2022-11-02], [x-ms-creation-time, Fri, 26 Jan 2024 20:35:33 GMT]...}

RawContentLength : 971

---

curl "https://sapene.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep?se=2024-01-31T00%3A00%3A00Z&sp=r&sv=2022-11-02&sr=b&sig=<redacted>"

StatusCode : 200

StatusDescription : OK

Content : {116, 97, 114, 103...}

RawContent : HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-MD5: FSTNbSlPBSO94KEc+i6Hdw==

x-ms-request-id: 51deeac7-701e-0078-3a98-508227000000

x-ms-version: 2022-11-02

x-ms-creation-time: Fri, 26 Jan 2024 20:35:42 GMT

x-ms-lease-s...

Headers : {[Content-MD5, FSTNbSlPBSO94KEc+i6Hdw==], [x-ms-request-id, 51deeac7-701e-0078-3a98-508227000000], [x-ms-version,

2022-11-02], [x-ms-creation-time, Fri, 26 Jan 2024 20:35:42 GMT]...}

RawContentLength : 971

Now we see, that our “secure” container isn’t that secure. It seems, that we need to really block public access, if we don’t want anybody to be able to connect with a storage account. If so, let’s try to use service endpoints with one of our accounts to see the results.

Using service endpoint

To be able to configure service endpoints for a storage account, we’ll need to make some changes to the Bicep script. To be able to use the same module for accounts with different network configuration, we’ll pass virtual network rules as a parameter:

param parSuffix string

param parLocation string = resourceGroup().location

param parAllowPublicAccess bool = true

param parDefaultNetworkAction string = 'Allow'

param parVirtualNetworkRules array = []

resource sa 'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts@2023-01-01' = {

name: 'sa${parSuffix}ne'

location: parLocation

sku: {

name: 'Standard_LRS'

}

kind: 'StorageV2'

properties: {

accessTier: 'Hot'

allowBlobPublicAccess: parAllowPublicAccess

networkAcls: {

bypass: 'AzureServices'

defaultAction: parDefaultNetworkAction

ipRules: []

virtualNetworkRules: parVirtualNetworkRules

}

}

resource saBlob 'blobServices@2021-06-01' = {

name: 'default'

properties: {}

resource saBlobContainer 'containers@2021-06-01' = {

name: 'test'

properties: {

publicAccess: 'None'

}

}

}

}

This allows us to decide if we want to give access to a specific network, or just ignore the parameter and let other settings define the access. Using virtual network rules isn’t directly related to service endpoints though. In order to specify a service endpoint, we need to add it on a subnet level. To give us more flexibility, we’ll introduce a dedicated subnet for service endpoints:

param parLocation string = resourceGroup().location

resource vnet 'Microsoft.Network/virtualNetworks@2023-06-01' = {

name: 'vnet-ne'

location: parLocation

properties: {

addressSpace: {

addressPrefixes: [

'10.0.0.0/16'

]

}

subnets: [

{

name: 'default'

properties: {

addressPrefix: '10.0.0.0/24'

}

}

{

name: 'serviceendpoints'

properties: {

addressPrefix: '10.0.1.0/24'

serviceEndpoints: [

{

service: 'Microsoft.Storage'

}

]

}

}

]

}

}

output outSubnetId string = vnet.properties.subnets[0].id

output outSubnetServiceEndpointsId string = vnet.properties.subnets[1].id

Now, what we need to do, is to limit access to one of the storage accounts using created service endpoint:

module sa2 'modules/storage-account.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'sa2'

params: {

parSuffix: 'se'

parLocation: parLocation

parDefaultNetworkAction: 'Deny'

parVirtualNetworkRules: [

{

id: vnet.outputs.outSubnetServiceEndpointsId

action: 'Allow'

}

]

}

}

As you can see, instead of the initial definition of a module, we’re taking advantage of new parameters. In short - we disabled public network access by changing the default action to Deny and defining a subnet, from which communication will be accepted. Now, for the storage account I have service endpoint defined, requests from my local computer start to fail:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Error>

<Code>AuthorizationFailure</Code>

<Message>This request is not authorized to perform this operation.RequestId:71078caa-f01e-0005-1a9c-50c0d9000000Time:2024-01-26T21:16:29.5787804Z

</Message>

</Error>

Before we test the connection using virtual machine, let’s explain the first confusion, quite popular for service endpoints. As you could see, we don’t define a service endpoint on a service level. In other words - for a service like Azure Storage (or any other similar PaaS service), there’s no magic “service endpoint” parameter. Instead, you need to perform two actions:

- enable service endpoint on a subnet level

- whitelist connections from a given subnet on a certain service instance

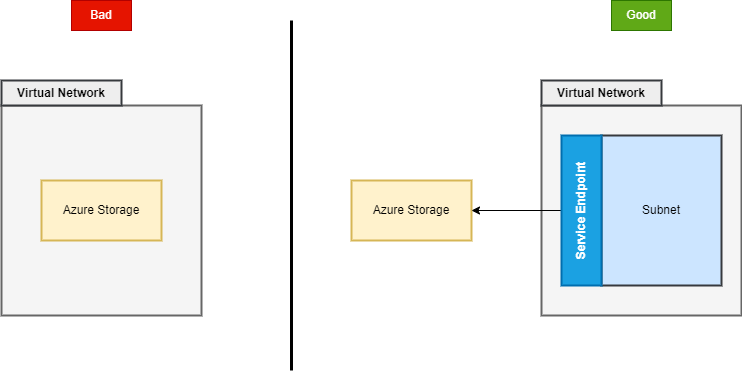

This means, that two instances of the same service, don’t necessarily allow the same connection - as you cannot deploy e.g. Azure Storage into a virtual network, it won’t accept connections from a subnet until you explicitly whitelist them. Such confusion is often visible on architecture diagrams:

While I treat the visualization on the left as acceptable (because conceptually I understand the author’s intent), it may be confusing for people, who don’t know the technical details of how service endpoints work. If you stick with the diagram on the left, people may think, that you actually deploy Azure Storage inside a virtual network. This might also imply, that such setup prevent accessing the account by anybody, who’s outside a network (assuming there’s not publicly available point of entry). I’ll show you shortly, that it’s not the case.

Checking connectivity inside a network

In order to connect with a virtual machine, we need to expose a selected communication channel. While in real-world scenarios I’d go for solution like Azure Bastion, in our sandbox network security group with port 22 (SSH) exposed will work just fine:

resource nsg 'Microsoft.Network/networkSecurityGroups@2023-06-01' = {

name: 'nsg-ne'

location: parLocation

properties: {

securityRules: [

{

name: 'ssh'

properties: {

priority: 1000

access: 'Allow'

direction: 'Inbound'

protocol: 'Tcp'

sourcePortRange: '*'

destinationPortRange: '22'

sourceAddressPrefix: '*'

destinationAddressPrefix: '*'

}

}

]

}

}

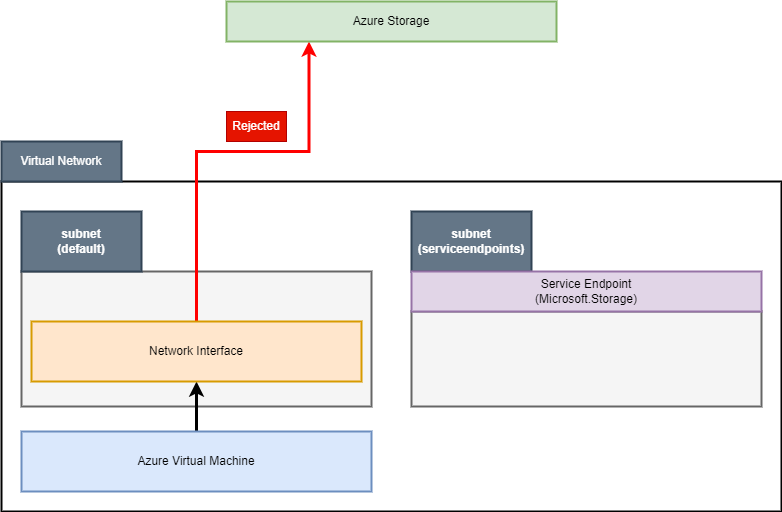

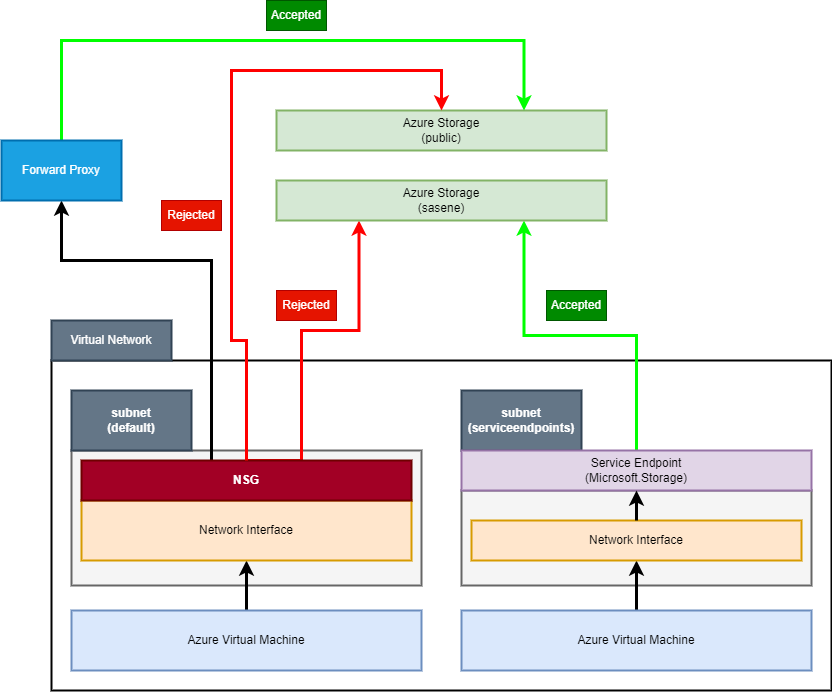

Now, let’s connect with a machine and see if it can access storage accounts. We’ll use the same method with curl to simply call the HTTP endpoint and get a response. However, when calling the storage accounts, the one which we reconfigured to accept connections from only a specific network, still returns an error. Let’s visualize communication:

As for now, it works as expected. Our storage account isn’t configured to accept connection from the

As for now, it works as expected. Our storage account isn’t configured to accept connection from the default subnet and as we can see, the connection isn’t flowing between subnets. We can perform one more check by deploying additional virtual machine - this time with a network interface attached to the subnet with the service endpoint:

module vm 'modules/virtual-machine.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'vm'

params: {

parLocation: parLocation

parSubnetId: vnet.outputs.outSubnetId

}

}

module vm_se 'modules/virtual-machine.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'vm_se'

params: {

parLocation: parLocation

parSubnetId: vnet.outputs.outSubnetServiceEndpointsId

parSuffix: 'se'

}

}

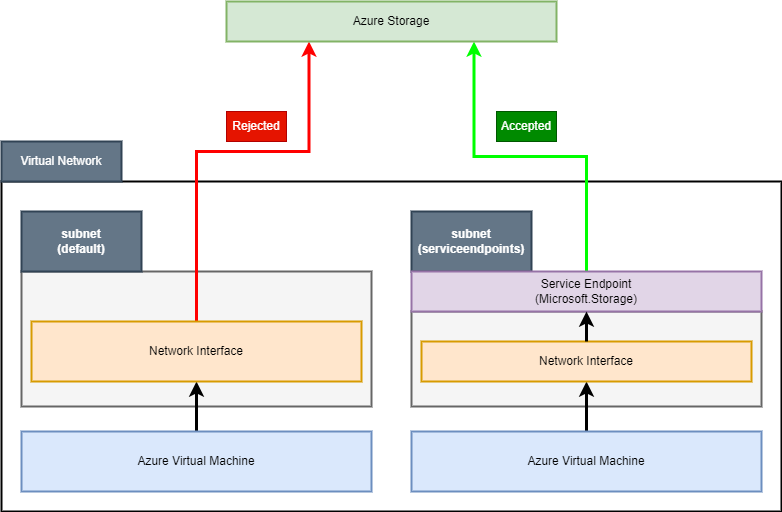

If everything is configured correctly, second virtual machine should have access to the storage account. When we rerun scripts used to validate access to storage accounts, we’ll see, that all 3 accounts are accessible to it. Once again, we can visualize the whole setup as so:

We were able to correctly configure our infrastructure to give access to a specific storage account using a service endpoint. We’re allowed to connect to it using a virtual machine, for which network interfaces resides inside a subnet with those endpoints. The question is - how network interface of a virtual machine knows, that connection should flow through an endpoint?

We were able to correctly configure our infrastructure to give access to a specific storage account using a service endpoint. We’re allowed to connect to it using a virtual machine, for which network interfaces resides inside a subnet with those endpoints. The question is - how network interface of a virtual machine knows, that connection should flow through an endpoint?

System routes in Azure

Each subnet in Azure contains a default route table with systems routes inside it. Those routes are meant to give you the basic routing functionality:

- if a source address is an address from within address space of a virtual network, the next hop is set to the virtual network itself

- if the source address prefix is 0.0.0.0/0, then the next hop is Internet

- for address prefixes like 10.0.0.0/8 or 172.16.0.0/12 the connection is dropped

You can read more about routing in Azure here - https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/virtual-network/virtual-networks-udr-overview

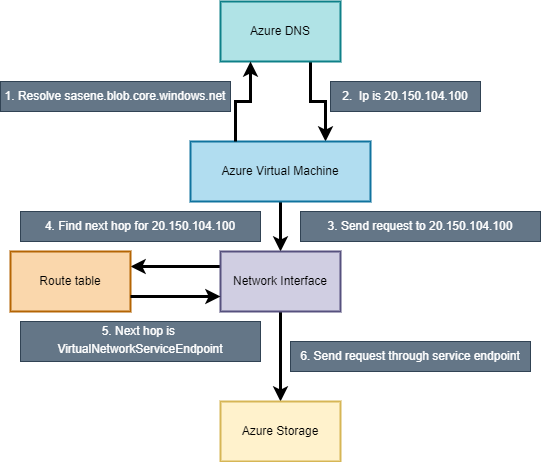

The important thing for us is the fact, that Azure will automatically provide additional routes if service endpoints are enabled. If that’s the case, a route table of a subnet will contain the public IP address of a service, for which an endpoint is enabled. This is what serves the security purpose of service endpoints - when they’re enabled for a subnet, communication between services is staying within Azure network backbone (as system route ensures, that the next hop in that case would be a public IP address of an Azure service). From the DNS perspective however, it doesn’t matter from where a connection is made - DNS address is always resolved to a public IP address:

nslookup sasene.blob.core.windows.net

Server: 127.0.0.53

Address: 127.0.0.53#53

Non-authoritative answer:

sasene.blob.core.windows.net canonical name = blob.dub09prdstr02a.store.core.windows.net.

Name: blob.dub09prdstr02a.store.core.windows.net

Address: 20.150.104.100

This means, that the communication flow of a virtual machine connecting to a storage account via service endpoint looks like this:

It’s also possible to check default routes, seeking the public IP address of our storage account. After close examination, we could find the following entry there (I removed most of the address prefixes for visibility):

It’s also possible to check default routes, seeking the public IP address of our storage account. After close examination, we could find the following entry there (I removed most of the address prefixes for visibility):

| Source | State | Address prefixes | Next Hop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default | Active | 191.235.255.192/26;191.235.193.32/28;…20.150.104.0/24;… | VirtualNetworkServiceEndpoint |

It’s also worth noting, that IP addresses of services in Azure may change. Azure takes care of that by automatically updating system routes each time public IP address of managed service, for which service endpoint is enabled, changes. For now the whole setup should be pretty clear and straightforward. I’m afraid however we still haven’t been able to answer the most important question - if service endpoints don’t switch communication from public to private IP addresses, and still incorporate public IP address of our services in a route table, what’s the fuss all about? Let’s focus on that for a moment.

Communication between services with service endpoints

We managed to establish the following traits of service endpoints:

- they don’t disable public IP address of a managed service

- we enable service endpoints for a subnet instead of service, what means, that multiple instances of the same service will use the same endpoint

- once enabled on a subnet, they inform Azure to add a dedicated hop, which points to a public IP address of a service

- the dedicated hop is one of they key security features of service endpoints, as it ensures, that communication stays within a network and goes through an endpoint

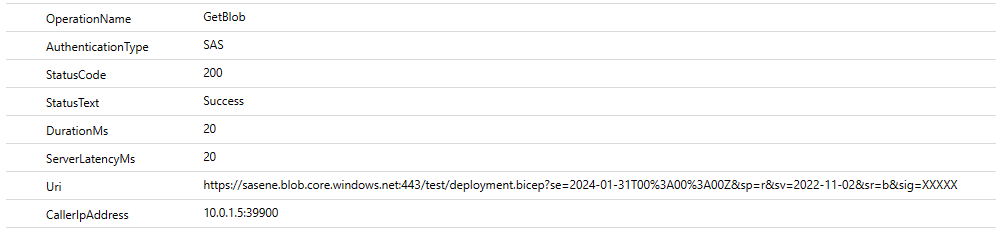

The last feature is especially important as it means, that our services are allowed to use their private IP addresses in communication with a managed service behind a service endpoint. We can easily verify that by enabling diagnostic logs on a storage account, to which we’d like to connect using service endpoint:

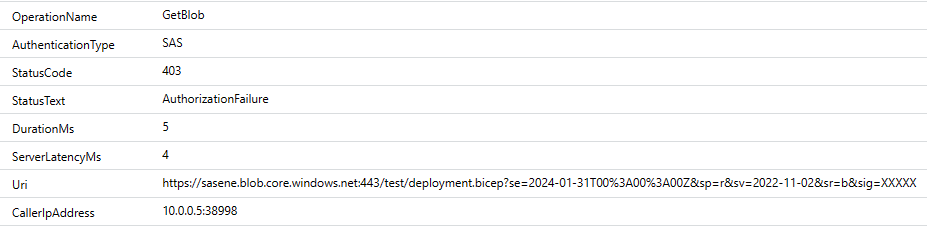

As you can see, the value of a CallerIpAddress property is set to 10.0.1.5, which is a private IP address of a virtual machine that has a network interface integrated with the subnet with service endpoint. The interesting fact is, that even if we call a storage account (for which default public access is disabled meaning, that it accepts connections only from whitelisted subnets and IP addresses) using a virtual machine, which doesn’t have access to a service endpoint (because its network interface is in another subnet), it’ll still use a private IP address:

This time however, the connection is rejected - storage account doesn’t accept it because the communication comes from neither a whitelisted subnet, not whitelisted IP address.

You could try to fix the connection problem between the second virtual machine and storage account by whitelisting its private or public IP address. This won’t work because IP firewall on storage account doesn’t accept private IP addresses as input. What’s more, as the connection doesn’t use public IP address, whitelisting it won’t have any affect.

The fact, that the second connection is rejected, is a proof, that we’re able to control who or what can call a service. This though is indirectly guaranteed by service endpoints. In fact, the whole setup relies on two elements:

- service endpoints giving the ability to route traffic to a public IP address of a service as a next hop in a route table

- service’s firewall, which allows you to accept connection from the full address space of a given subnet

This shows us, that while service endpoint are indeed a solution to consider when building a solution in Azure, they may not be granular enough to cover all the cases. If you expect your services in Azure to be accessible only by a subset of applications or machines inside a virtual network, you could find service endpoints to be insufficient. On the other hand, there are possibilities, which could help us isolate managed services with service endpoints a bit better. Let’s discuss them.

Securing communication between services with service endpoints

As service endpoint isn’t a feature, which is configured per instance of a service, it doesn’t give you the possibility to secure communication with enough granularity. There are however some options, which we could consider to somehow limit the number of possible network flows.

Service tags

The first idea we could think about are network security groups and service tags. Such setup could potentially disallow connection between our virtual machine and storage account, even if service endpoints are disabled for a subnet. Note, that this idea is far form ideal:

- service tags work for all services of a given type globally or per region, hence you still cannot limit access to an individual instance of a service

- it doesn’t use service endpoints, so it doesn’t really matter if you use them or not (of course - in the context of the networking between services)

- depending on the placement of a network security group (network interface or a subnet), achieving enough granularity may be quite annoying, as you would need to introduce individual rules for each IP address of a service inside a subnet to control what is allowed, and what is forbidden to connect

- service tags will work only for outbound connectivity controlled by a network security group - they won’t prevent e.g. a forward proxy, which could be outside a network, from connecting with a managed service (though you could argue, that this is what service endpoints are for)

When visualized, such setup will look like this:

As you can see, we could limit access to storage accounts without service endpoints, but it still means, that we lack granularity. What’s more, as mentioned before, such limitation is easy to omit by introducing an external component, which won’t be covered by NSG rules. Ideally we’d just route traffic from the first virtual machine to service endpoint in the second subnet, but as for now, Azure doesn’t allow such routing rule.

All right, it seems, that service tags and network security groups aren’t going to help us in better communication security when using service endpoints. There’s however one more component, which we could check to see, if it can help.

Service endpoint policies

If you seek additional layer of security for Azure Storage, you could consider using service endpoint policies. This is quite an interesting feature, as it enables you to tell Azure to which storage accounts given subnet has access to. While it may look trivial initially, you’ll quickly see, that it could be a game changer in some scenarios. To get started, I’ll deploy a service endpoint policy using the following definition:

param parLocation string = resourceGroup().location

param parAllowedStorageAccountId string

resource sep 'Microsoft.Network/serviceEndpointPolicies@2023-06-01' = {

name: 'sep-ne'

location: parLocation

properties: {

serviceEndpointPolicyDefinitions: [

{

name: 'sepdef-ne'

properties: {

service: 'Microsoft.Storage'

serviceResources: [

parAllowedStorageAccountId

]

description: 'Storage service endpoint policy definition'

}

}

]

}

}

This definition accepts a parAllowedStorageAccountId parameter, which we will use to tell Azure, to which storage account we’d like to allow connection. Now, I’ll add one more storage account, which will use the existing service endpoint:

module sa4 'modules/storage-account.bicep' = {

scope: rg

name: 'sa4'

params: {

parSuffix: 'se2'

parLocation: parLocation

parDefaultNetworkAction: 'Deny'

parVirtualNetworkRules: [

{

id: vnet.outputs.outSubnetServiceEndpointsId

action: 'Allow'

}

]

}

}

Note, that currently Azure Resource Manager doesn’t support creating subnet association for service endpoint policies. To complete the setup, you need to use Azure Portal, Azure PowerShell or Azure CLI.

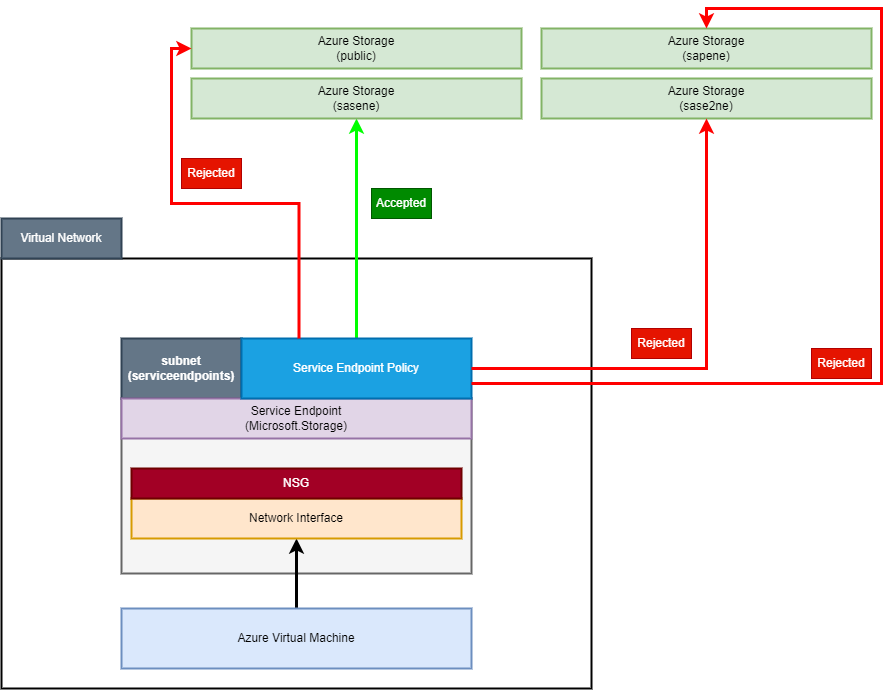

After deployment completes, we can test the connection. In short, we have 2 storage accounts with the same whitelisted subnet, so, conceptually, one of the virtual machines should be allowed to make connections to both. The validation script looks like this:

#!/bin/bash

sas1=`az storage blob generate-sas -c test -n deployment.bicep --permissions r --account-name sapublicne --expiry 2024-01-31T00:00:00Z | jq -r .`

sas2=`az storage blob generate-sas -c test -n deployment.bicep --permissions r --account-name sasene --expiry 2024-01-31T00:00:00Z | jq -r .`

sas3=`az storage blob generate-sas -c test -n deployment.bicep --permissions r --account-name sapene --expiry 2024-01-31T00:00:00Z | jq -r .`

sas4=`az storage blob generate-sas -c test -n deployment.bicep --permissions r --account-name sase2ne --expiry 2024-01-31T00:00:00Z | jq -r .`

curl "https://sapublicne.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep?$sas1"

curl "https://sasene.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep?$sas2"

curl "https://sapene.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep?$sas3"

curl "https://sase2ne.blob.core.windows.net/test/deployment.bicep?$sas4"

The result can be a little surprising:

- sapublicne - REJECTED

- sasene - ALLOWED

- sapene - REJECTED

- sase2ne - REJECTED

Huh, it works even better than expected, doesn’t it? Let’s visualize our setup:

What’s interesting, access to sase2ne storage account is blocked even though it has explicitly whitelisted connections from servicendpoints subnet. This means, that service endpoint policies takes precedence over other methods of limiting access to Azure Storage. Access is blocked also for sapublicne storage account, which is a publicly available service (no service or private endpoints). We can now clearly see, that this is a great data exfiltration prevention method. The only downside is, that it currently works only with Azure Storage.

Summary

As you can see, service endpoints are a simple and useful solution for introducing additional layer of network isolation when it comes to managed services in Azure. They may be not ideal due to their limitations, but still find their place as a baseline network security model, even in the simplest architectures.

Service endpoints pros

- no infrastructure needed to deploy and configure them

- free - you use them with no additional charges incurred

- ensure network traffic stays within Azure backbone network

- allow hybrid (public + private) connection models - useful everywhere you don’t want or cannot use VPN (e.g. development environment)

- with service endpoint policies can be easily configured to secure from data exfiltration

Service endpoints cons

- not granular enough - you are unable to restrict access to individual managed services (with a single exception for Azure Storage)

- require additional level of governance and security to ensure, so their hybrid connection model isn’t abused

That’s the end of the first part of my deep dive about service and private endpoints in Azure. In the next article, we’ll focus on the latter to see what are the differences between both endpoints and the best use cases for both of them.